I recently experienced a minor medical mystery in the form of a skin infection on my wrist. Appearing pretty much from nowhere (probably vectored on a mosquito…I blame trying to watch the Orionid meteor shower), this was originally diagnosed as a bacterial infection. Despite two rounds of antibiotics, it didn’t improve, slowly growing into what looked like someone had stuck a lit cigar onto my wrist. It didn’t actually hurt or itch very much aside from being a bit tender.

In the end, it turned out to be a fungal infection. Easily treatable with modern antifungal creams1…but this got me thinking about the lot in life for pretty much everyone who lived before the early 20th century. Not just in terms of sheer mortality, although there’s that, but also just the annoying accumulation of minor diseases that are easily treatable now, but more or less permanent then.

Fungal infections are kind of interesting. Note, I’m no medical researcher, so take what I say here with some salt. However, my impression from digging around a bit is that the human immune system is good about keeping most fungi out, such that fungal infections are rare outside of immunocompromised individuals. However, those fungal infections that do make their way past the immune system are very resilient to the immune response and often don’t go away on their own. I presume many of the “open sores” one reads about in historical accounts would have been more or less permanent fungal infections2.

The dreaded athlete’s foot (ringworm…not actually a worm), a common and highly contagious fungal infection of moist areas of the body, particularly the foot and groin3, is the classic example. The condition can be painful and debilitating, but typically isn’t fatal. Easily treated with modern medicine, it doesn’t usually go away on its own.

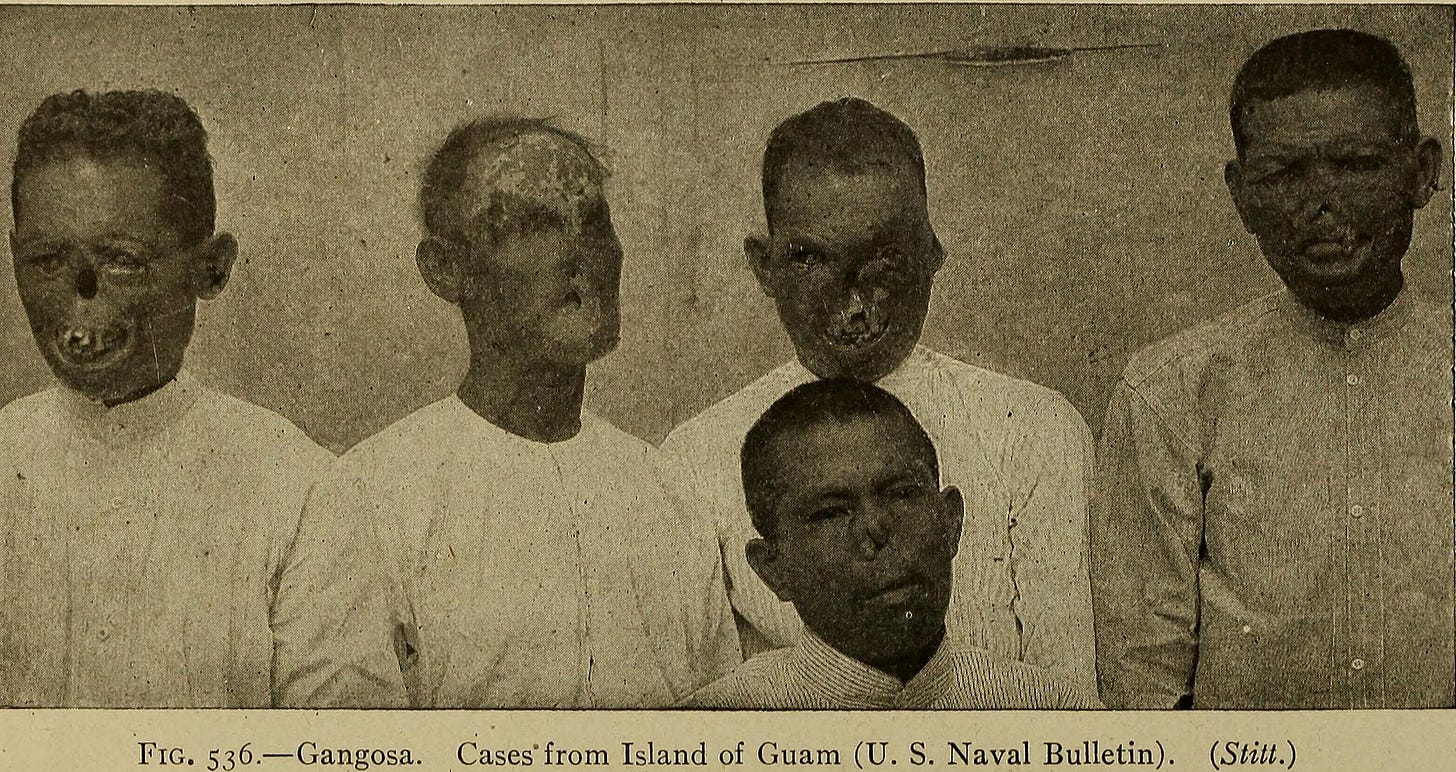

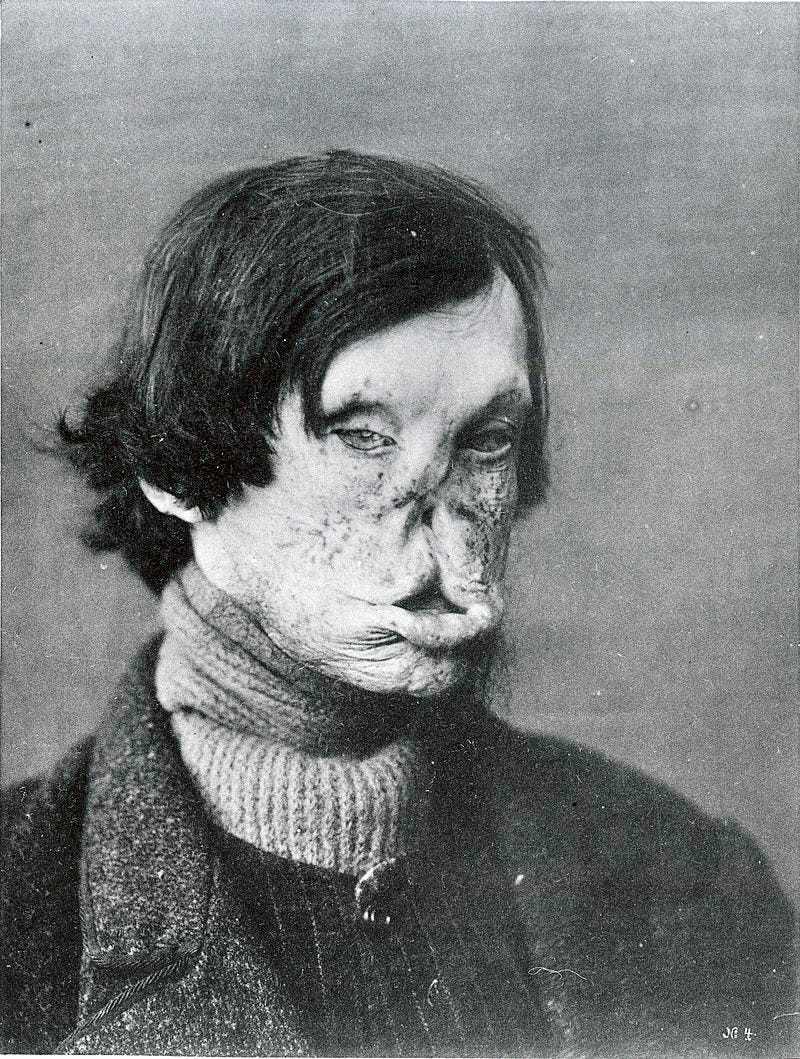

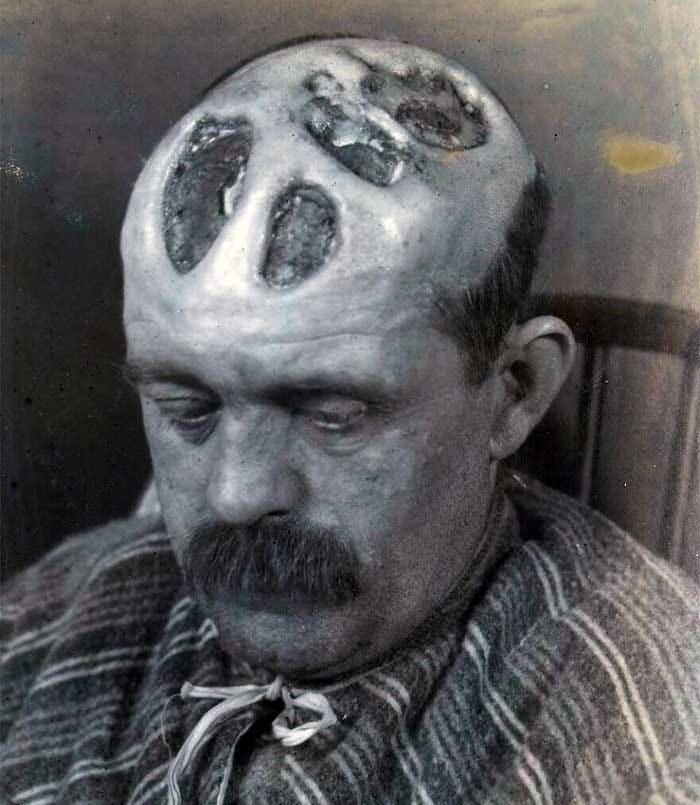

Infections seem to fall into four broad categories. First, those that make you sick but go away without treatment. Common colds and many bacterial infections fit into this category (though some, like Covid19 may kill some individuals with weaker immune systems). Second, are infections that kill us outright, such as smallpox, anthrax, Ebola, etc. Third, are infections that come and go, often hiding dormant within the body such as syphilis, or chicken pox/shingles. Lastly, are chronic infections that typically don’t kill, but linger indefinitely causing discomfort or disfigurement. Bacterial infections such as leprosy and yaws and tuberculosis (albeit this latter does eventually kill) would fit into this category, as do many fungal infections.

Of course, some of those other categories are very important. Not dying from infections is good…one need only look around in an old cemetery to see how many young people were carried off by infections prior to the creation of modern antibiotics in the early 20th century. Suppressing or eliminating dormant infections also improves quality of life.

But I’m particularly interested for the moment in the latter category of chronic but (mostly) non-fatal illnesses. These must have been a common feature of pre-20th century life and that must have sucked. These must have accumulated gradually over the lifespan, as sometimes attested in autopsies of mummies, making quality of life miserable for many.

Consider that modern antibiotics weren’t created until roughly the 1930s with the advent of Sulfa Drugs. Before that, a chronic infection could become more or less permanent. The dreaded leprosy is a classic example (although it’s historical use may have referred to a variety of skin dissolving illnesses including leprosy or Hansen’s disease, tertiary syphilis, yaws, etc.) Leprosy is curable today with a rigorous antibiotic regimen, but a disfiguring and stigmatizing illness in the benighted before times.

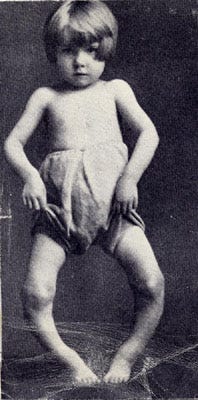

I’m not sure if there’s anything like a prevalence study of archaeological illnesses, but historical records document a past marked by chronic illness. Prior to the modern age, people appear to have been riddled with parasites and chronic infections, eye and teeth damage due to infections were common, broken bones might lead to permanent loss of function, dietary deficiencies would lead to scurvy and rickets, etc. I think about this when people sometimes glorify “indigenous” medicine (by which here I mean anything from any part of the world before modern medicine), as some kind of naturopathic approach. The outcomes may have been better than nothing, but were still pretty bad.

I don’t want to paint the pre-modern age as entirely incompetent in medicine, of course. Even our earliest tribal ancestors developed some effective remedies via trial-and-error and many of our modern medicines are direct descendants of those earlier efforts. We owe those proto-scientists a debt of gratitude. But so too did pre-modern medicine often offer false hopes, whether folk medicine based mainly in wishful thinking or the brutal, often poisonous4 and anesthesia-free medicine of pre-modern European practice5. I remember hearing the story of a physician who had to sit through a surgical procedure removing a tumor from his neck, with no anesthesia at all. Blessedly, it seemed to have been a reasonably brief surgery and he survived, but the through of enduring that today is remarkable.

Perhaps future generations will look back on our present day of harsh chemical interventions and bloody surgery and thank the stars they didn’t have to put up with our medicine. And to be sure, many chronic conditions remain untreatable into the present day. But I do think it’s worth remarking on how relatively lucky we are to have lived in the relatively recent age of modern medicine.

Annoyingly, I would end up with two stiches due to a skin biopsy. Ultimately unnecessary I suppose since the dermatologist simultaneously did the biopsy and prescibed the antifungal cream…which worked.

Note: where possible I have used public domain/open license/creative commons images. Others are credited as best I could, and used under my understanding of “fair use”. None of the images originate with me.

Though, as I learned, can take root pretty much anywhere.

European physicians likely often did more harm than good using metals such as lead as medicine.

Modern use of anasthesia only began in the 1840s with ether and chloroform.