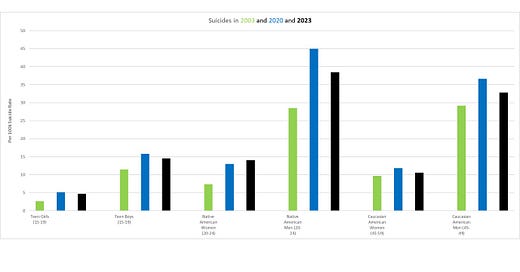

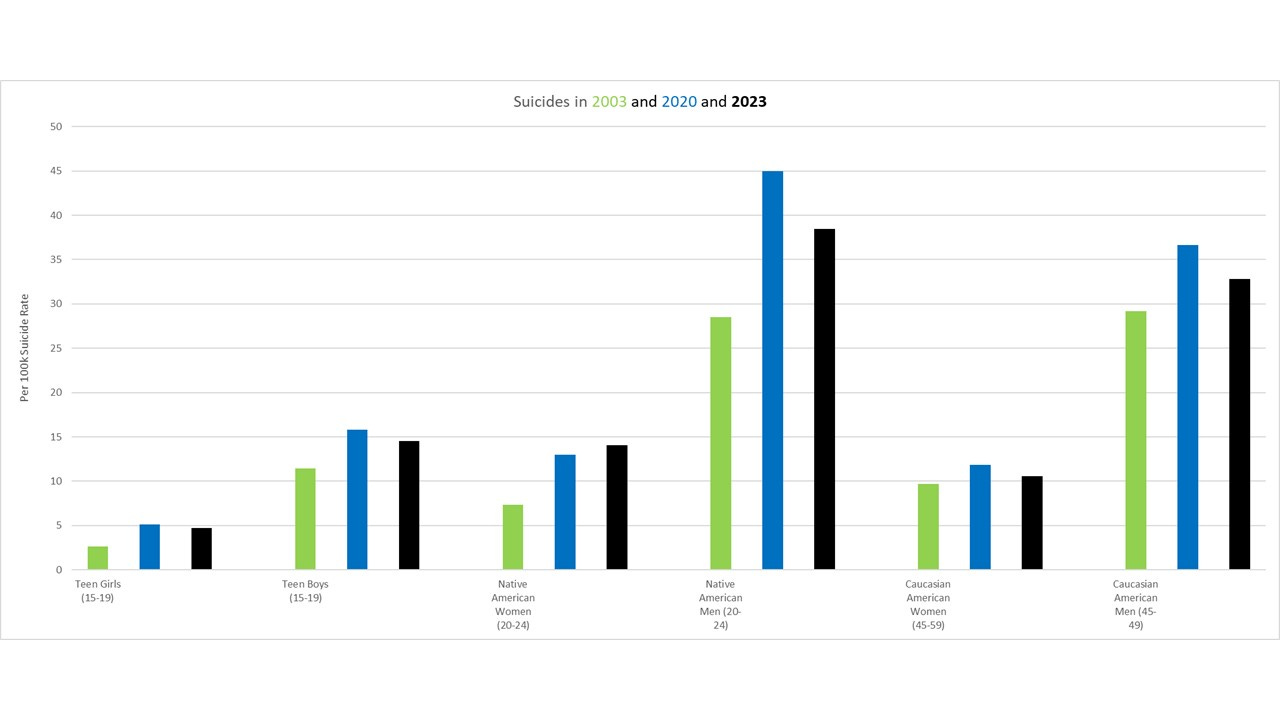

The last 5 years, if not more, has seen the US and other countries like the UK gripped by the narrative that there’s a youth mental health crisis. That’s not actually true…there’s little evidence of a crisis at all in most European countries. For the US, there definitely is a mental health crisis but, if anything, it’s most pronounced among two groups…middle-aged white men, and young American Indian men. Not teen girls, who actually commit suicide about the least often of any demographic group.

We can see this best in suicide data (self-report data, often the lifeblood of teen mental health panics, turns out to be entirely unreliable, and even hospital data has been corrupted by changes in reporting over time). These suicide data shown below are updated to 2023, the latest CDC data. Several things that are important to note. First, almost all groups’ suicide rates appear to go both up and down in tandem. Second, suicide rates for middle aged Caucasian men, and young American Indian men are far higher than for teens, and also increased more dramatically from 2003 to 2020 than did teens’ rates, in terms of absolute numbers. Lastly, with the exception of Native American women, most groups’ rates went down between 2020 and 2023. And these decreases happened without any substantial censorship of smartphones, social media, etc., which youth still use as much as they ever have.

This data is pretty clear…mental health is not an isolated teen problem. What happens to their parents’ generation is associated with what happens to kids’ generation. Trying to separate youth out, so as to better blame technology, was a critical, horrible mistake that has wasted much time and policy effort.

We can also see this in CDC data from youth self-report (the youth risk behavior surveillance system). In the past, youth screen time was basically not a predictor of youth mental health problems. But 2023 was the first year that the CDC included a question about social media specifically. As I wrote about before, the CDC found that, even in essentially bivariate correlations lacking proper statistical controls, relationships between social media and youth mental health were trivial, basically at the level one would expect from statistical noise.

By contrast, another report from the CDC did discover what appears to be related to youth mental health issues: basically, their families. The CDC asked youth a series of questions about adverse events in the household…being abused, neglected, or having parents with mental health problems or who had been incarcerated. Compared to the wispy social media effects, relationships between these adverse childhood events and self-reported mental health outcomes were robust. For example, experiencing 4 or more such events (as compared to 0), was associated r = .346 with self-reported depression/sadness, r = .521 with suicidal ideation and r = .570 with suicide attempts1. By the standards of weak social science, these are robust correlations. Even in an absolute sense, correlations in the .5 range are impressive, explaining at least 25% of the variance in the outcome2.

To be fair, this is once again based on self-report data and, as with all self-report data, should be taken with serious salt. But this suggests we should largely ignore the whole social media panic, and, if we’re really serious about teen mental health, should focus on what teens are clearly trying to tell us. The problem is originating from within the house.

Put simply, when parents have problems, those problems appear to trickle down to their kids. This shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Unfortunately, it seems no one is really paying attention to this fairly obvious data, including the CDC. Talking about family abuse and dysfunction just doesn’t seem “sexy”, and parents don’t want to hear that any issues their kids may be having have a decent chance of originating with them. One isn’t going to sell a bunch of books or get on Oprah with that uncomforting message. Parents prefer magic wand explanations: that with one sweep of policy, kids’ problems will magically go away and, conveniently, parents themselves were never at fault.

What’s remarkable, however, is just how glaring this data is, and how easily available it is. And nobody is talking about it.

I take these from Table 4 in the CDC report, converting ORs to r using this converter: https://www.escal.site/

The other big contributors to youth problems appear to be genetics, which is not exactly a target for public policy unless we fancy CRISPRing our way out of youth depression, and peer issues such as bullying.