Not ALL Social Science Stinks.

A quick look at the Big 5 Personality Theory and what it can teach us about reliable social science.

I complain quite a bit about psychological and social science research1. Typically I wave my fist at the sky about both the lack of rigor and overselling of weak findings. A lot of social science research is bad, very bad, not-good-at-all, reaks of dirty socks bad. Even that which is methodologically sound, most often tends to produce results that are unreliable or trivial, so much so we can’t even be sure the results are real as opposed to statistical noise or “crud”. This does raise the question though of what sound psychological research looks like. Surely, there must be some examples?

I’ve chosen to highlight one field I actually think is pretty sound. Not that every study is great, by any means, but overall, this is a field that has replicated cross-culturally and consistently produces effect sizes outside the trivial range. Namely…drum roll please…the Big 5 Personality Model.

If you’re not familiar with it, this model suggests that there are 5 broad elements to each of our personalities, with each of us along a high to low range on that trait. The 5 traits (which can be remembered using the OCEAN mnemonic) are:

1. Openness: This is basically a willingness to try new things coupled with less judgement toward different ways of doing things. Individuals high on this trait may be more adventurous, enjoy traveling to different cultures, and less likely to express anger at those with different political, moral or religious views than themselves. Someone puts a plate of zebra brains in front of this person in a foreign restaurant? They’ll give it a try.

2. Conscientiousness: Basically orderliness, neatness and a preference for following the rules. People high in this trait like lists and instructions, everything in its place and would be less comfortable winging it or stretching the rules. If your soup cans are arranged alphabetically, this may be you.

3. Extraversion: Involves a preference for being around others rather than being alone. This is not the same thing as shyness…one can be a shy extravert. Rather, this reflects a preference, albeit it is often coupled with outgoing behavior. Individuals high in this trait prefer to find themselves the life of the party rather than staying home with a good book. Social whores.

4. Agreeableness: This trait reflects a tendency to keep the peace, avoid confrontation and treat others with kindness and respect. Folks high in this trait likely come across as generally nice, friendly and helpful. The rare London resident who will stop to give tourists directions.

5. Neuroticism: Reflects a tendency to worry and ruminate. This trait is likely the origin point of many mental health concerns ranging from anxiety to depression to body dissatisfaction. If figuring out all the details of your vacation causes you more stress than just staying at work, this may be you.

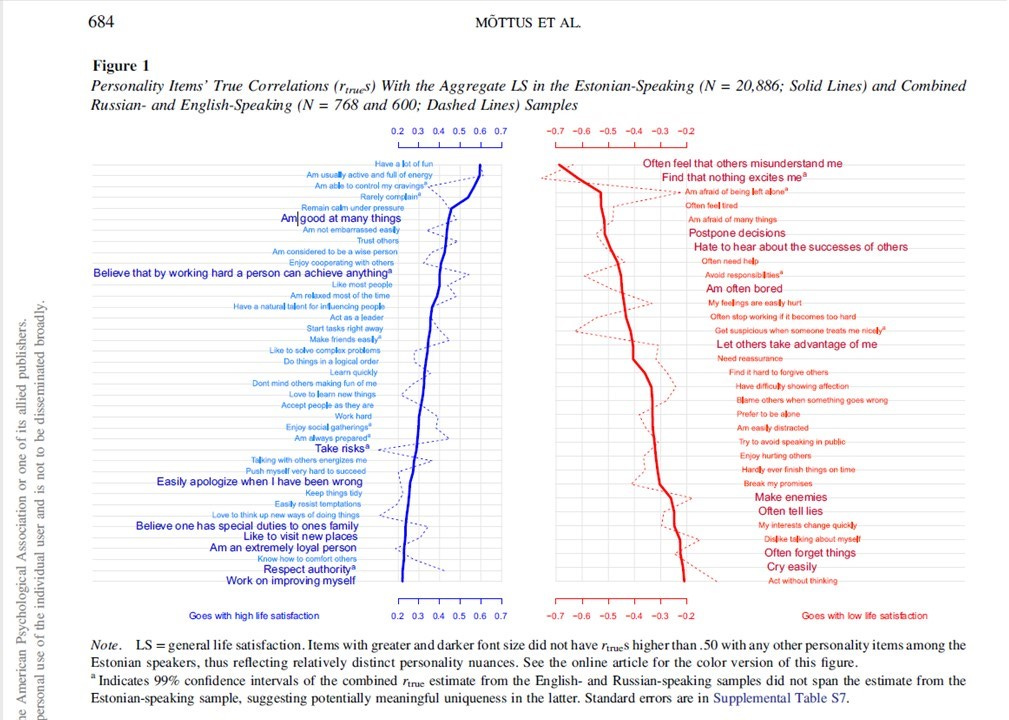

A study released last year on the Big-5 reflects the research on this. This study found that, taken together, Big-5 traits correlate up to a whopping r = .8 or so with general life satisfaction outcomes. In the social sciences, that’s huge. Individual traits correlated lower (neuroticism, not surprisingly, as well as extraversion and conscientiousness tended to stand out) with life satisfaction, but correlations for most of those were still above the noise/trivial threshold. Even more skeptical studies find fairly similar results, though some suggest that maybe using subfacets of the Big-5 traits would be better than using the broader traits.

This is just one study out of many on the Big-5 that goes back decades. This field provides a template we may be able to use to judge the utility of social science findings.

1. The findings reliably replicate in the most rigorous studies. Further, the findings replicate cross-culturally. Granted, there are some population differences we expect (men and women are substantially different, inmate populations will differ from the general public, etc.) But if we see a lot of neurotic hand wringing about how sample differences may explain unreliable results without some clear (and not post-hoc) theory as to why, that should be a red flag2.

2. The effect sizes are substantial. The Big-5 doesn’t predict everything of course. But finding predictive studies with correlations in the .3, .4 or higher range are common. The Big-5 actually predicts people’s behavior in meaningful ways. A correlation coefficient of .2 should probably be a hard cut-off before we get too excited about the usefulness of a social science finding. And anything below .10 shouldn’t be taken seriously at all. Aside from the replication crisis, distinguishing noise from signal is probably the most pressing problem for social (and medical3) science. We need more rigorous and hard standards, but it’s nice to find a field regularly exceeding them.

3. The stats are pretty simple. Over the past 50 or so years I suspect social science has defensively relied on an increasingly complicated array of endless statistical models, designs and gizmos to hide the basically unreliable nature of noisy data. I suspect this has mainly been a mistake (but hey it keeps the statisticians off the streets). The more complicated the statistical model, particularly for a dataset that could have been analyzed with a basic regression, the less I trust the results these days. Data shouldn’t have to be cloaked in statistical voodoo to impress us (or subdue us into silence).

So, hat’s off to the Big-5 and this theory is a reminder that social science does have something to tell us about the human condition when it’s done right. Of course, I’d love to hear from you as well. What fields of social science do you think live up to high standards of rigor with impressive findings?

More frighteningly, the same problems extend to medical science, which is something nerve-wracking to consider on each doctor’s visit.

This is, in fact, a very common and vastly overused explanation for unreliable research results. “Oh, we, it didn’t replicate because the samples are different!” To be fair, that may be true in some isolated instances, but this rationalization is grossly overused. Besides any finding that is so fragile to even minor sampling differences maybe isn’t that worthwhile anyway.

I’m honestly nervous to think how many medical decisions are based on weak effect sizes from massive sample correlational studies in the medical sciences which aren’t at all uncommon.

Some issues also exist for personality science as it mainly relies on statistical models, which you also seem to criticise in this article. But even when considering that, it does seem that personality science is one of the more reliable fields in psychology.

I think that both cognitive and behavioral psychology (old rivals) seem reliable on a larger comparative scale.

I think a lot of psychometrics has something useful to offer, but also has a lot of crap in the mental health sector and organizational psychology.

Some organizational psychology also seems redeemable, like predictors of job performance, Goal-Setting Theory (sounds a tad bit pseudo-profound though, as this is very common sensical).