Most Social Science Research is a Waste of Time

Not because it's bad (though much is) but because many researchers don't really act like they care about the results...

Recently I did some work on a dataset involving roughly a million criminal justice cases. As part of this I ran a table of bivariate correlations between multiple variables. As some stats-minded people can already guess, almost every single variable was correlated with almost every other variable with p – values below .05 (most of them below .001). Scanning the numbers, the smallest “statistically significant” correlation was r = .008. Such a tiny correlation is almost certainly statistical noise, not a “real” effect. Even if it were “real” (which it almost certainly is not), it would mean that the variables predicted roughly 0.0064% of the variance in one another (or put more crudely, if you wanted to predict one variable from the other, your odds of doing so would be roughly 0.0064% better than chance1).

This is a gaping hole in how we conduct social science. I imagine most social scientists might intuitively know that taking a correlation of .008 seriously as hypothesis support would be ludicrous (although increasingly, I’m less and less sure of this generous assumption). But what is a problem is we have no real guidelines on how to interpret weak effect sizes. We can be pretty sure that correlations below r = .10 are indistinguishable from noise and should never be used for hypothesis support (though people still do this all the time). But that doesn't mean r = .11 is solid evidence. I start to get convinced that, for a good study, r = .20 and above probably aren’t noise (or at least not only noise), but truly good studies are themselves hard to come by2.

But the reality is, although controversies over the interpretation of effect sizes have raged since before I’ve been alive, most scholars still interpret whatever the hell passes the p = .05 “statistical significance” line as a binary hypothesis support threshold, come whatever may. There are, in fact, plenty of defensive arguments in the social science about how any effect size could be important3. This is nakedly self-serving given that most social science effect sizes are very weak, typically below r = .20, and often below r = .10. The result is that the social sciences are certainly guilty of massive misinformation on human behavior, misinformation which has wasted millions if not billions in taxpayer funded research, and numerous wrong turns on everything from mental health to education to the military.

This should be an incredible, embarrassing scandal. But it’s not because the general public doesn’t know what the hell an effect size is and most of the people drinking from the gravy bowl don’t want the gravy to stop. The honest truth is that, during my lifetime, there have been no real reliable, fundamental breakthroughs in our understanding of human behavior, because social science is mostly spinning its wheels making big tadoos about crappy results. There are exceptions…off-hand, I’d say there’s some real powerful work in personality traits, behavioral genetics, sex differences, the impact of IQ on life outcomes and maybe a few other areas. But they are islands in a vast sea of wasted time.

And yes, of course this makes it easier for social science to get lost down moral rabbit holes like wokeness, technopanics4, or whatever. When you’ve got no standards of rigor, it’s easy to confirm almost any damn belief you have so long as you ignore the ephemeral nature of most social science research findings.

My point, to be clear, is not that achieving weak results or null results is a waste of time. Far from it. It’s good to know what’s not important, what doesn’t work, even what’s just so trivial we needn’t worry about it, etc. It becomes a waste of time when we ignore these bad outcomes to celebrate whatever hypothesis we had all along, so long as the magic “statistical significance” line of p = .05 gets crossed.

To illustrate this problem a bit, I asked ChatGPT to create some hypothetical scatterplots (with 500 cases) for different correlation coefficients. Here’s the scatterplot it generated for r = .7, which would be a strong correlation:

There’s obviously some variance in the data, but the cases follow a clear pattern, as illustrated by the red line running through them (the line of best fit). Theoretically with a new case, you could make a reasonably accurate prediction of one variable based on the other. For instance, if someone scored a -1 on the Y axis variable, you could draw across and then down and reasonably guess they’ll score somewhere in the range of -1.5 on the x-axis variable. Similarly if a new person scored a 2 on the Y-axis variable you can reasonably guess that person will get somewhere in the neighborhood of a 3 on the X-axis variable. Those predictions aren’t going to be perfect, as the individual cases (the orange dots) don’t perfectly align along the red prediction line. But generally, people who score lower on Y are also going to score lower on X and vice versa. This is the basis of how prediction works, say using IQ tests to predict school GPA, which tends to have correlation coefficients of about .7, meaning such tests are pretty (but not always) effective5.

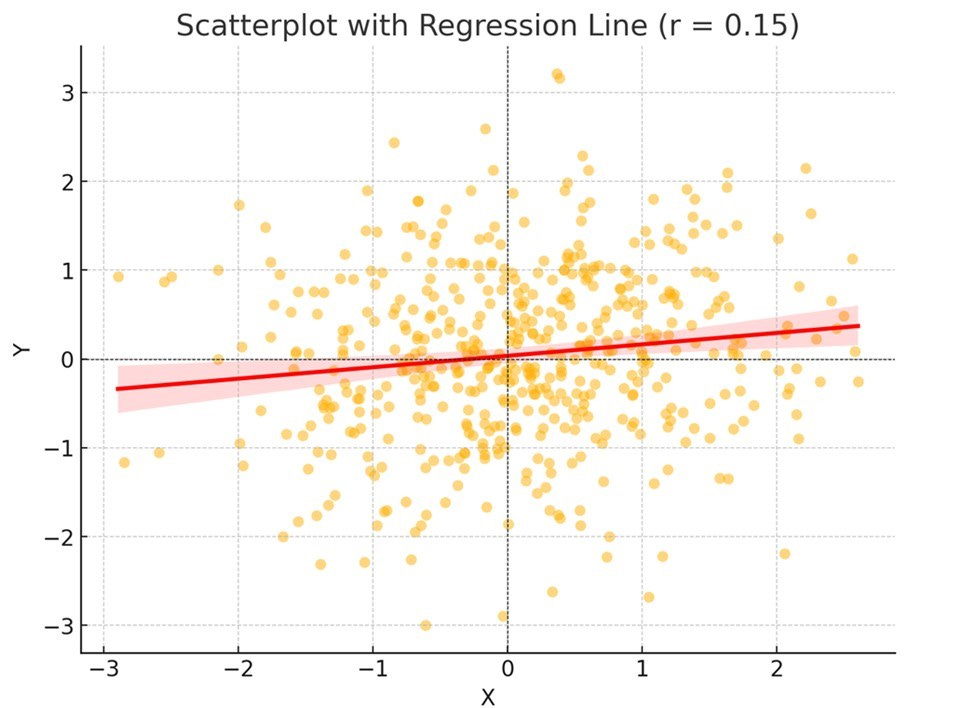

By contrast, here’s a hypothetical scatterplot for r = .15, a fairly median effect size in the behavioral sciences:

In this case the plot follows no particular order. Some low scoring Y-axis scores also score low on the X-axis, but some actually also score very high on the X-axis! You’ll also see the line is too flat, such that it’s difficult to use it to predict anything. Basically, quite frankly, this is useless noise, absolutely worthless in trying to understand human behavior. Yet, most social science studies find effect sizes like this, can achieve “statistical significance” with a big enough sample size, and often proclaim outcomes like this as if they were groundbreaking findings deserving of public policy. And do keep in mind something like r = .15 is the median effect size in published research papers (most of which claim hypothesis support), so many published correlations are much worse than this.

I think there are several things that contribute to this state of affairs.

First, I think it’s just human nature to be excited about our hypotheses and have a bias for them. I want to be upfront here…to the degree I’m being critical, I don’t exclude myself from this criticism. I’m sure there are many examples in my own work where I haven’t been as conservative in the interpretation of effect sizes as I should have been. No matter how much we talk about the interpretation of effect sizes, p < .05 (i.e., “statistical significance”) always feels like we’ve reached the brass ring and any critical thinking can stop. Being able to say, “Well I achieved statistical significance, but based on this effect size, I still don’t think my hypothesis is supported” is a tough conclusion to reach. This is a culture/awareness thing not a people-are-bad thing.

Second, publication bias (the preference of journals to publish findings that support hypotheses and reject those that don’t) is still a thing. Even in the era of open science, most published paper don’t use open science principles like preregistration (one recent article estimated about 7% for preregistration). Given that academic jobs remain primarily dependent on research articles, this creates perverse incentives not only for questionable researcher practices/p-hacking that can lead to false positive results, but also irresponsible hyping of weak results.

Third, I think our field is simply defensive. People get into this field to find cool and important results about human behavior. To admit that most of what we do accomplishes no such thing is understandably embarrassing. It’s not worth the public funding of grants. It’s not worth newspaper headings. It’s not worth the dinner table conversations. So…much of psychology and social science is like the “big fish” story…the fish gets better with every telling until we get to the point we’re not even sure there ever was an actual fish. How humbling it is to dedicate one’s life to studying something yet conclude that understanding that thing remains largely outside our grasp.

When I say that most of social science is worthless, I don’t mean there’s no point in conducting these studies. Actually, finding out that humans are so complex that finding important predictors of their behavior is exceedingly difficult is an interesting finding in and of itself. But social science becomes worthless when it functions as a mindless exercise in collecting messy data and producing ephemeral results, yet simply interpreting them in the most grandiose way in accordance with our preexisting biases.

Unfortunately, that’s what we’ve become. And I don’t know how to fix it.

This way of explaining shared variance likely grates on statisticians’ nerves, but I find it a helpful way to assist the general public in getting a sense of this in a tangible way.

In a bad study, which abound in the social sciences, any effect size could be nonsense.

One classic is the idea that a terribly weak effect size, if only sprinkled like pixie dust over a large population of individuals, suddenly becomes relevant. There’s no evidence at all for this belief. And, since most human psychology deals with all humans, it doesn’t take long to figure this argument could be used to defend any effect sizes from almost any study.

Wokeness and technopanics really originate from a lot of the same spaces, something a fair number of the anti-woke fail to realize.

The validity of IQ tests at their basic task of predicting school performance is one of the shining lights of the social sciences. It’s ironic that so many social scientists hate IQ tests or even the concept of intelligence.

Unfortunately, I agree with this assessment. I even think it applies to medical science as well. Not the effect size problem as much, but that most of it is pointless due to a large collection of methodological problems, statistical problems and sample collection problems. I read an article that looked at quality assessment of 2500 systematic review studies and 6% of those studies were of good quality and around 10 % was of moderate quality. This used the GRADE assessment tool, which, if done poorly, can be misused. Nonetheless, even if a small portion of those studies is overestimated or underestimated, does not diminish the severity of the problem.

I get the "small effect sizes can still matter on large populations" excuse from mostly only social scientists, and it's so very naive and annoying, as they rarely exclude the possibility of those effect sizes being due to problems with their methods, with the statistics or even what sample got collected. The claim is extraordinary as they can only point to a small subset of examples where it seems that interventions with small effect sizes seem to matter in large populations, and have no reliable evidence to support this notion on every occasion they point to this, when their small effect sizes should also matter. Sure, small effect sizes can sometimes matter, but only when the best possible body of evidence has excluded the more likely alternative hypotheses and explanations, when the effects replicate reliably and so on. This rarely happens as replications are still very rare in psychology, and exploring many possible alternative explanations to exclude alternatives also rarely happens. Which means that the claim that their small effect sizes of their pet-theories are on a majority basis, either a naive assumption or a self-serving excuse. And I think Furgeson mentions that here as well. And this shows something very annoying in psychological science, and that is a lack of genuine skepticism about findings. Which is both sad as skepticism should be an important building block of science (maybe even a pillar).