Schools Move to Ban Smartphones...Despite No Evidence Such Bans Will Work

The problem with schools is schools. They're dull.

A few times recently I’ve given talks about moral panics, how they develop and how they are sustained. Moral panics, which tends to focus on youth (or sometimes women or minorities), are complicated things. They typically identify “scapegoats” for a perceived social problem, while simultaneously helping people feel morally superior. Many of them, such as the current smartphone panic, focus on new media and technology. They often cater to older adults who control social levers simply by buying newspapers, voting and (via wealthier individuals), having money for research and academic grants. Thus, moral panics also tend to die with those older generations (which is why nobody is suing Ozzy Osbourne today as they did in the early 90s).

One common issue with moral panics is the tendency to try to put solutions into place, before there’s even clear evidence there’s a problem or that the proposed solution will work. The way I’ve presented that in recent talks is:

People have a good intention (maybe…)

They start doing a thing…

That thing turns out to be a colossal mistake…

They keep doing it anyway…

Why?

This always interests me, this cycle, as I think it helps to explain why people become very hostile to good news when it comes to moral panics. For instance, if parents are worried about smartphones, and we present them with evidence smartphones aren’t the source of kids’ problems, some parents get angry. I think that part of this is because the moral panic made people feel good about themselves as champions of righteousness. Or at least that the fights they picked with their kids were for a good cause and not, god forbid, a senseless conflict where it turned out the kid was right. Some of the people I see get angriest and most defensive when presented with good news are those who take to public forums (ironically including social media and smartphones) to loudly proclaim what good parents/teachers/administrators they are by preventing kids from using smartphones.

But also I think the tendency to act first and worry about evidence later is part of the problem. Hence, the trend for some schools to try to ban smartphones. As the smartphone panic has heated up, these seem to be increasing in popularity. In part, I think this is because there is little perceived downside…if it turns out smartphone bans don’t help, well at least they probably won’t hurt (although more on this in a bit).

At the same time, I do think this creates sunk costs and a tendency to persist with useless policies even when it’s clear they don’t work. Let’s go through the points above.

I don’t doubt most teachers/administrators have good intentions when they propose smartphone bans. But the problem these bans are trying to fix are ill defined. As I covered in a recent essay for The Hill, outside the US, there’s little clear evidence youth are even experiencing a problem that needs fixing. By contrast, the US does appear to have an issue with increasing mental illnesses, but that’s true for all generations, not a teen thing. In fact the worst outcomes are for middle aged adults. So we’re starting with a poorly conceptualized problem.

At present, there’s no good evidence smartphone use predicts mental illness, nor that reducing their use improves mental health. For that matter, student standardized testing has been largely static, and evidence doesn’t suggest that the presence of smartphones has much impact on attention or cognition. And…there’s no good evidence smartphone bans work.

Nonetheless many schools seem to be skipping to #2…put in a solution for an ill-defined problem, despite little evidence the solution will help. This is because, on one hand, I think there’s a genuine motivation to do the “right thing” even in a clueless way. But also the social and personal moral boost is itself incentivizing. In other words, yes I’m saying there’s some selfish motive, but I mean this in a very human non-judgmental way. It’s just how humans think.

Of course, once the policy is in place, now those teachers/administrators own it, so backing down can mean losing face. Thus, people are incentivized to ignore evidence the policy isn’t working and keep it in place…sometimes even if it is doing harm.

There are exceptions to this. In South Korea, about a decade ago, policy makers put in place a video game shutdown law, essentially preventing minors from accessing online gaming from late evening through morning. Like smartphone bans, this probably seemed intuitively appealing to parents. But like smartphone bans, it simply didn’t work and had no perceivable impact on youth wellness. To their credit, Korea eventually repealed it, though much attention and money was expended uselessly in the process.

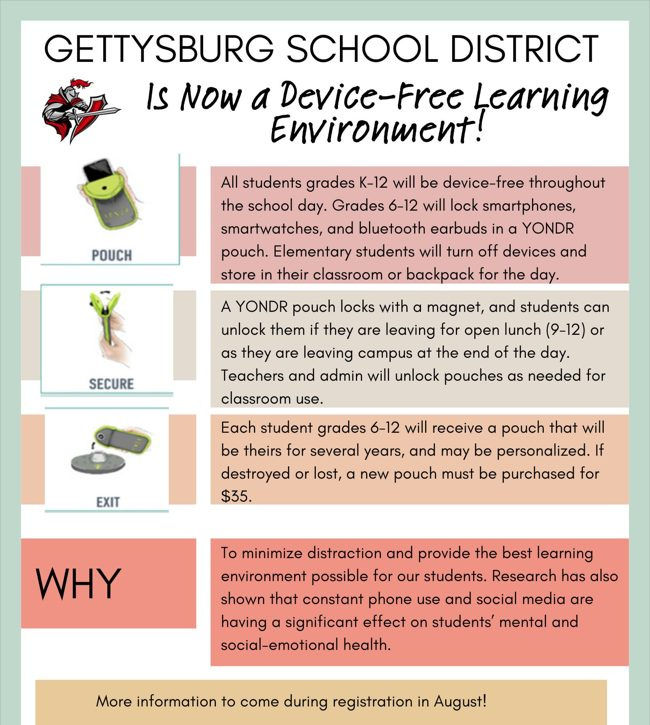

I think we’re already at #3 on the list…at least insofar as evidence suggests caution in implementing unproven policies. Yet, people are charging ahead, apparently ignorant (as the school district in Gettysburg, ND) of the actual research evidence.

Which brings us to the costs of these programs. I agree students probably don’t benefit in any particularly way from having a smartphone in class, even if the phones don’t hurt them (we were fine without smartphones in the 70s and 80s). But bans require enforcement, and that requires time, resources, and confrontations. It’s unlikely all students are going to go quietly along with these bans. Do the bans increase confrontations between students and teachers and parents? Do they increase detentions and suspensions? Could they actually have a negative impact on student well-being? People haven’t even really considered the costs of such programs.

More to the point, the bans feed the illusion that students would be naturally attentive to teachers if only smartphones weren’t present. Again, there’s no evidence for this. Back in those woebegone 70s and 80s, we didn’t pay attention to teachers either…we slept, doodled, daydreamed, wrote or scratched on the desks, talked to other kids, etc. We didn’t need smartphones not to pay attention. I suspect smartphones mainly irritate teachers since they are very visible evidence of student boredom. But they’re not the cause of inattention.

The main problem for schools simply is so much of teaching is simply boring. The problem with schools is schools. That’s always been the case, though it may have worsened under the “No Child Left Behind” standardized testing craze of the 2000s. The idea that taking smartphones away will result in placid youth attentively taking notes is a middle-aged adult fantasy. Again, there’s no evidence this will work…and no evidence smartphones ushered in an age of particular problems, given the basically flat standardized testing scores for youth since the 1970s.

Unfortunately, aside from investing resources into enforcement and creating conflict with students, the fantasy of smartphone bans deflects schools from considering real ways to increase student engagement with learning. That seems like the real tragedy here for me.

Nonetheless, moral panics aren’t sensible things. People will put in place policies because they feel good, not because they have good evidence such policies actually work. At the best, smartphone bans will simply be a waste of time. At the worst, they may put increasing enforcement demands on teachers, and increase discord between kids and adults.

Chris, your arguments are solid and personally I don’t need data because 1) I’m convinced that our problems today are way bigger than smartphones because that is what my common sense tells me and 2) I know how hard these things are to measure so any data would probably suck anyways. However, when you say there is no evidence, I think it’s important to distinguish evidence that shows that cellphones are not bad for kids vs. absence of evidence, meaning that we don’t have anything yet.