The close of a new year can be a time for reflection…what went well and what went poorly in the prior year and what we hope for in the year to come. With that in mind I’ve chosen to do my final essay of 2024 on an issue on which I feel I’ve goofed. Specifically, an article from 2022 claimed that, in effect, conservative adolescents appear to be more resilient to mental health concerns than progressive adolescents. This got a lot of press attention in 2023 particularly (and not surprisingly for either side) from conservative news media. Given the meltdowns in progressive structures from 2020 on1, this story fit with my priors2 and, on reflection, I didn’t give it the scrutiny I should have. So…let’s take a look.

First, I want to note that I’m mainly criticizing myself here, not really the study authors. My deeper read of the study, which itself is based on the well-known Monitoring the Future database, a large national sample of youth and adults, is that it’s probably not very good. But, in fairness to the authors, it’s not very good in a way that most social science is not very good (in other words, it’s kind of “meh”, but only because most social science kind of sucks)3. But I didn’t do my due diligence when I first heard of the study and gave it a more preliminary read. Clearly, I should have, and I hope pointing this out is revealing how we can all have blinders when a research study tells us a good “story” we’re already primed to hear.

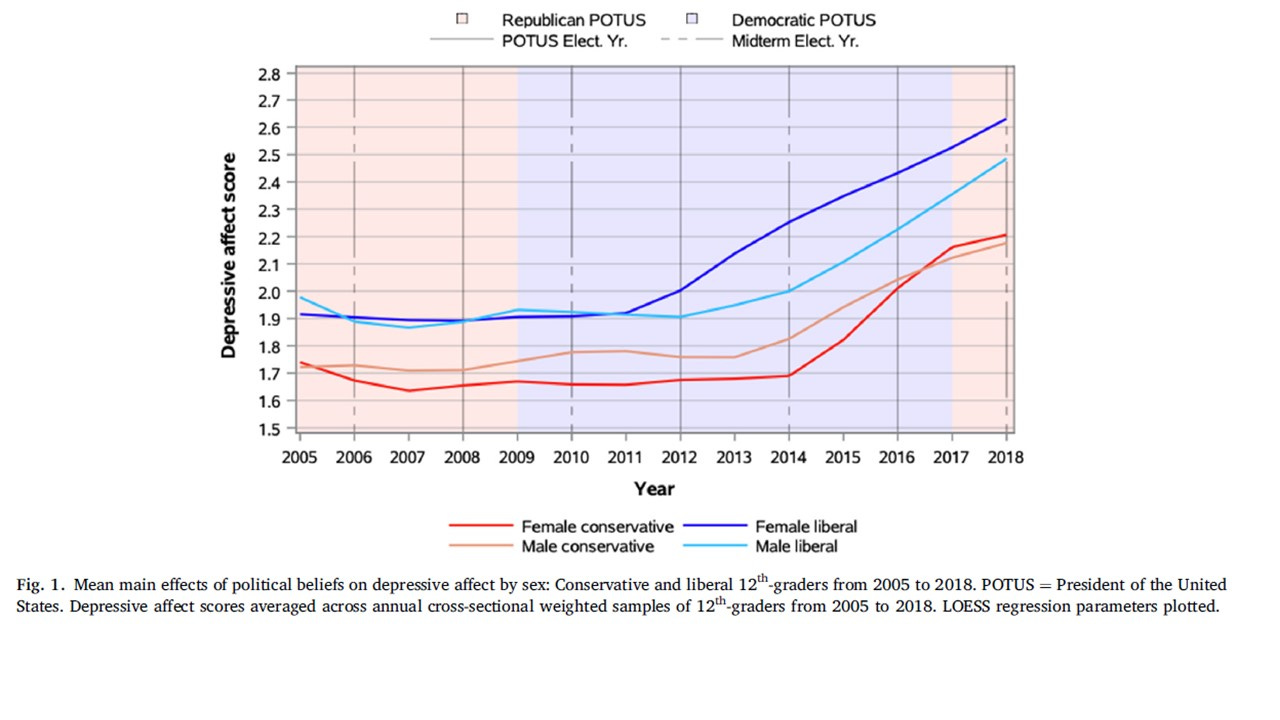

The study itself is basically a correlational study of 12th graders, examining depressive mood related disorders (including self-reported depression, self-esteem, self-derogation and loneliness) and how they related to self-identified politics, as well as a host of control variables4. What I think raised a lot of eyeballs was a graph showing depressive affect levels among conservatives and liberals. As the authors themselves put it in their conclusions: “In conclusion, we found that worsening time trends in adolescent internalizing symptoms from approximately 2010 onward diverged by political beliefs and were most severe for female liberal adolescents without a parent with a college degree.”

Even looking at the graph perhaps one could raise a few objections. A lot of visual magic can be done with the manipulation of Y-axes and probably the pattern would look less dramatic had the Y-axis represented a full range of scores (which as I understood, they took mean values so that should be 1-5). Even the highest scores are somewhere around the midpoint of the scale, so we’re not talking a ton of depression here. But I’d say that’s a quibble…there’s probably some difference there. The graphs for the other outcomes aren’t so different either that I’d think the authors cherry-picked this one, so good on them (some study authors do, indeed, cherry-pick their results).

But these are basically bivariate effects being presented with no controls…and we should always be wary of that. People interpreted this graph, I think, as an indication that liberal youth were more nuts than conservative youth. And, again, that fit with a story emerging out of 2020 about “snowflake” youth, trans youth and kids who hated their country, embraced Communism, etc. But maybe these kids are different in other ways than just their political values. Or maybe these kids even interpret the questions differently.

Where things get interesting, though, is when the authors do multiple regressions controlling for other variables. Here the story falls apart. Controlling for other variables, the correlation between political ideology and depression is a measly r (beta) = .105. For the other outcomes, the effect sizes were even worse (-.07. .04 and .04 for self-esteem, self-derogation and loneliness). Interaction effect sizes for female liberals, the group everyone seems most worried about, were basically zero (rs between .02 and .04). Effects for parental college degree were similarly unimpressive (.07) suggesting there’s not much there either. As I’ve pointed out many times before, effect sizes this small cannot be reliably distinguished from statistical noise. Basically, this is a nothing result.

Inevitably, some social scientists will raise the “Wait, but aren’t even small effect sizes meaningful when applied to a big population?” argument. There’s probably no bigger source of heartburn for me6 than this obviously self-serving bit of nonsense that, along with p-hacking, is primarily responsible for keeping social science well within the realm of pseudoscience.

Of course, there are lots of other pretty glaring problems here. The responses are self-report and may reflect both cultural and historical trends in the reporting of mental health, not real changes. I’m not really sure how well-validated clinically these scales are. There’s single-responder bias and demand characteristics, which can cause at least small false correlations (one reason we shouldn’t trust small effect sizes). Increasingly, I’m becoming wary of how the Monitoring the Future dataset is being (mis)used to say things about teens I’m increasingly skeptical of.

I imagine (maybe?) the study authors might agree with me on some points at least, perhaps saying something like “Well, we didn’t mean political ideology per se predicts mental health, but rather it interacts with a bunch of other historical stuff going on.” Indeed, I think with a generous read of their study, they were probably trying to say this. But maybe they could have been clearer about that in the abstract, which is the bit of any study news media will run the football with7. I also think some of the historicity of this particularly stupid moment in our culture means simply that liberal youth are probably a bit more comfortable talking about mental health than conservative youth, without that necessarily reflecting any actual underlying differences in their wellness.

I’m not sure how often I referred to this study in passing, but I’m sure I did. I let myself be fooled8. This study is yet another lesson in the perils of small effect sizes and how overselling them can misinform the general public as this study (unintentionally) did. But it’s also a reminder, for myself and for others, how easily fooled we can be when we want to be, even if it’s just because the story is “cool” as this one seemed. We should probably be more skeptical of cool-looking graphs, and be more alert to trivial/noise effect sizes. The burden of proof is always on those making the claim of an effect.

But sorry, conservatives…those blue-haired progressive kids are probably no more nuts than yours.

Which, to be fair, continue to the present day in academia.

I’m not a conservative, and still consider myself a 2012-era Obama progressive so I’ve got no skin in this particular game. However, it was hard to ignore that there certainly was a not of neuroses among people running liberal organizations and not unreasonable to suspect this could trickle down to kids, the most visible of whom seemed to become “traumatized” at the drop of a hat.

My general argument is less that we shouldn’t do it and more we should be more modest about what we do, myself included. I’m sure I’ve run afoul of my own advice plenty of times.

Yes, they included social media. In the supplementary Table A7, they included the results only for self-esteem and self-derogation which were not impressive (rs of -.05 and .02 respectively). I don’t see where they reported the outcomes for depression or loneliness, but maybe I’m having a stroke. At any point, the authors seemed unimpressed with the whole social media thing, writing about the field in general “Recent studies have focused on digital engagement and social media, but research into adolescent wellbeing and depression has not convincingly demonstrated that digital technology use is driving these observed trends…Technology use alone also cannot explain the apparent gender differences in internalizing symptoms over time as social media use among boys and girls is neither a strong nor consistent risk factor of depressive affect for either group.” I agree with them on that for sure!

As a reference, r = .00 is nothing at all, and r = 1.00 is a perfect correlation. But’s actually kind of rare to get an r = .00 exactly as both random and non-random noise tend to create small, messy effect sizes distributed around .00, although potentially with a skew favoring the hypothesis. So r = .01 is still likely no different from .00, as is r = .02, .03, .04, etc. The question becomes when we can reliably concluded assuming the study is methodologically good that we have an effect size substantially large enough that it’s unlikely to be due simply to noise. I generally don’t advise people to interpret effect sizes at or below r = .10 as hypothesis supportive even if “statistically significant”. Probably we should even adopt a more stringent r = .20 as a base meaningful effect size that is large enough both to be unlikely to be noise (unless the study is outright crap), and large enough to be minimially noticeable in a practically or clinically significant way.

And I eat a lot of spicy food and pizza.

As with all things, it’s easier to criticize than live up to one’s ideals. I think they just got excited with a novel result in much the same way I might have done had I been in their shoes.

And again, that’s on me, not the study authors.